For Payroll Director Kathy Rice, last week’s training on suicide prevention hit close to home. With teary eyes and Kleenex in hand, she expanded on her personal experiences with this topic.

“I’ve been thinking about [QPR training] a lot because I had a nephew that committed suicide. It’s important that people go to training like that because college age is such a vulnerable age for suicide,” Rice said. “When my nephew committed suicide, I didn’t see those signs that they discussed. 20 years later it’s still hard to know, ‘Did I miss something?'”

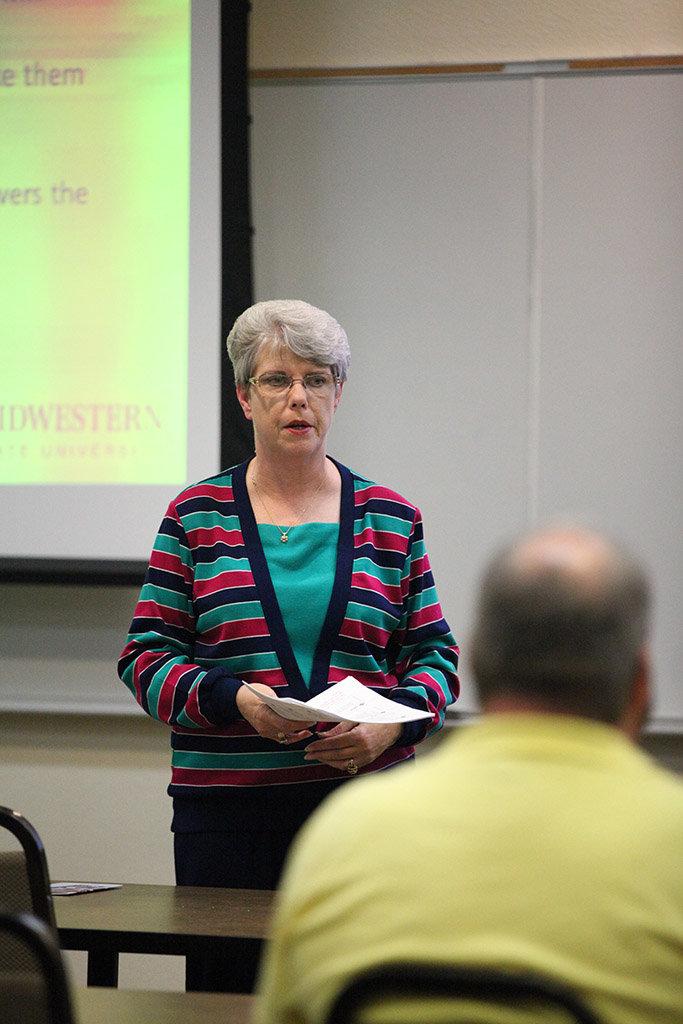

During the training, counselors Lori Arnold and Vikki Chaviers explained that sometimes the evidence of a suicidal person is obvious, but other times it’s hard to spot.

“The warning signs might look different to each person, but generally the number one thing to look for is signs of depression. The training teaches us that about 90 percent of people who attempt suicide are depressed,” Arnold said. “It’s a really important issue to address, especially since suicide can be very preventable. But the signs aren’t always obvious because people can mask their emotions.”

She expanded on the importance of asking someone if they’re thinking about suicide despite the common fear of bring up the subject. After all, according to the American Association of Suicidology, suicide is the second leading cause of death for individuals in the 18-25 age group.

“Sometimes we’re worried that asking the question can put the thought in someone’s mind, which isn’t true. Talking about suicide isn’t going to increase someone’s risk of doing it,” Arnold said. “It’s almost always scary and difficult to ask if someone is thinking about committing suicide, but it’s one of those situations where you have to take a deep breath, summon your courage, and just say, ‘Are you thinking about suicide or hurting yourself?’ or ‘Do you ever wish you could go to sleep and never wake up?'”

Arnold said they have been doing the QPR training (Question, Persuade, Refer — a nationwide training program to help create “gatekeepers” on how to look for signs of suicide and how to handle getting help) since fall 2013. It is offered to students and faculty at least once per semester, as well as special groups on campus such as residents, advisors, and campus police officers. Approximately six faculty and staff members attended the April 12 training session.

“If faculty and staff don’t go to the training, they might miss some of the signs,” Albert Jimenes, campus police sergeant, said. “It could be something small that a student may send in an email or some kind of reach for help, but if the professor or staff member doesn’t know what’s going on, we could miss giving them the help they need.”

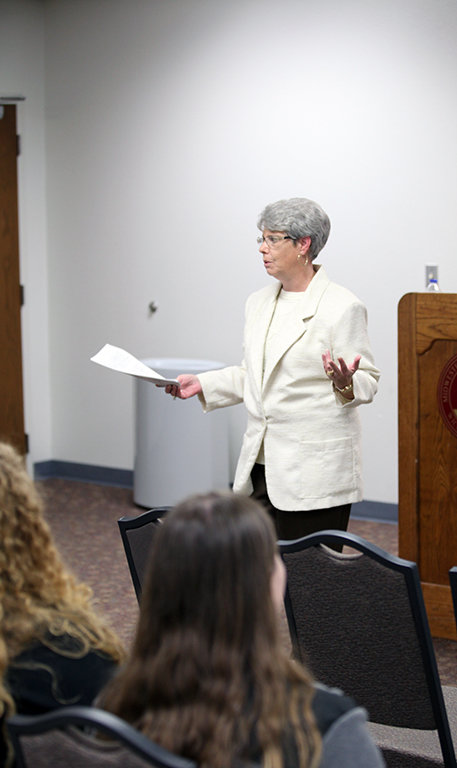

There were about eight students at the April 14 session, and upon the end of the workshop, they all became certified gatekeepers complete with a certificate.

Arnold said it’s important to cast a wide net of people who can look out for students who may be thinking about suicide, but training other students is also necessary.

“Professors and staff members are around students from time to time, and have some access to them, but the students are probably going to be around other students more than they are faculty and staff,” Arnold said. “The more people that are trained, the more people that can be helped.”

Rice, who attended the faculty QPR training, said that college students are at a vulnerable age for suicide because they can’t often see that their situation will improve.

“Students from the age of high school through college have a different view of the world than someone with more life experiences. So a lot of times, they don’t have that foresight to know that it’ll get better and that it’ll pass,” Rice said. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, things will get better.”

Whitney McDade, nursing junior, said she came because QPR was on one of her tests and she thought it would be cool to find out more.

“It’s cool that we’re certified gatekeepers,” McDade said.

Victoria Post, nursing junior, said she definitely feels more equipped now to handle a situation in which she might have to help a fellow student contemplating suicide.

“It’s stuff we’d covered in class, so we can feel assured we were getting the best information,” Post said.

Tips for suicide prevention included phrases to listen for when talking to a friend and how to ask them if this is something they are serious about without making them feel alone. Both McDade and Post said they had dealt with people who considered suicide in their personal lives.

“The best thing is, if someone says they are thinking about suicide the one thing that you always want to make sure is, ‘Do they have a plan?'” McDade said. “Because if they have a plan, then you need to really need to be willing to help them out, more so than someone who doesn’t have a plan.”

Arnold expanded on McDade’s point, emphasizing why both students, faculty, and staff should attend these trainings.

“You never know who someone is closest to,” Arnold said. “Maybe they’ll talk to their friend or maybe they’ll talk to a faculty member, so it’s important for as many people as possible to know the warning signs.”

Additional reporting by Kara McIntyre.

Read the rest of the mental health series articles:

Under Pressure: Anxiety is more common than you think

Suicide prevention training hits close to home

On-campus psychology clinic offers free counseling

Counselors: Nothing is off limits

Column: The best and worst day of my life

Column: Support, don’t condemn those with depression

QPR Training