COVID-19 Reporting at MSU: How accurate are the numbers?

The Bruce and Graciela Redwine Student Wellness Center and the Cinson Health Center are located on the water front of Sikes Lake, on the other side of campus, across Midwestern Parkway. Photo by Rachel Johnson

Midwestern State University releases an updated count of reported COVID-19 cases on campus every weekday. These reports provide an idea of what the COVID-19 situation is like for the whole of the campus population while also allowing the university to track trends.

“To the best of our ability, those are accurate and they are updated daily,” Interim President James Johnston said. “It’s to our benefit to make sure everyone is aware the most accurate number of cases possible because if you try to hide those, all we’re doing is perpetuating infection and spread.”

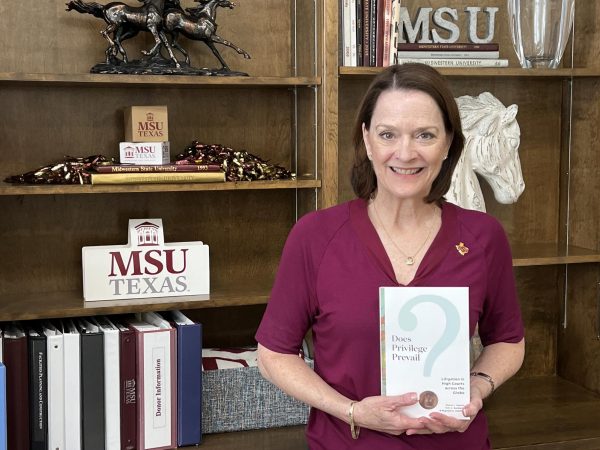

Every morning the reports are tabulated by Dr. Keith Williamson, medical director at the Vinson Health Center. Students can report cases in two different ways. The first is by self-report, which could be reporting a positive test or infected roommate and a need to quarantine. The other way is by a self-test, which Williamson says is more likely to be misinterpreted.

“If a student tests positive, the faculty are notified. If an employee tests positive, the area where they work is notified,” Johnston said.

Unlike last semester, not all colleges are participating in contact tracing, which is where students are provided with information on a COVID-positive student in their class. While some colleges, like the Dillard College of Business Administration, still have classes following this procedure, other colleges, like Prothro-Yeager College of Humanities and Social Sciences, aren’t allowed to.

“Part of the reason… is because the only test results we’re really sure about are the ones we hear about on campus. We get specimen, we send it off, we get the results. So we do contact tracing on those people,” Williamson said.

Caroline Gomez, political science junior, said the university culture around COVID-19 is more relaxed this semester. She also believes that the number of cases are being under-reported.

“They aren’t as adamant about checking in, I feel like, and someone might test positive but they aren’t getting their test from the Vinson Health Center,” Gomez said. “I would report it, but I think there’s a lot of people that don’t report it. They want to come to class.”

Williamson admits that he believes the numbers from the reports are not completely correct. He refers to serology studies over the last year reporting that for every one diagnosed and reported case, there are two cases unaccounted for.

“There is no doubt in my mind that our numbers are not complete and accurate… [But] they reflect the numbers in the community, which tells me I’m probably getting an accurate picture of activity on campus,” Williamson said.

Part of the inaccuracy could be due to students knowing they are positive but not reporting it. This could be due to several personal or occupational factors the person has to take into account.

“This disease has disparate impacts on people. The younger you are the less you have to personally deal with and you’ve got a job, school and deadlines… there are pressures,” Williamson said.

If a student reports a positive test or a need to quarantine from exposure, they will likely miss 10 to 14 days of school, work or life in general. While Zane Batson, art junior, said they would report themselves, they believes many students don’t.

“[People with symptoms are] probably not [reporting]. There are people who will but I think nobody wants to cause a panic so they’re gonna just keep to themselves,” Batson said. “I would [report myself if I had symptoms] because I work at Lowes and I come to such a public place. I know that affects a lot more people than just me.”

The Texas Department of State Health Services reports that one out of every 300 people in Wichita county have died from COVID-19. As of Sept. 25, there were 2,114 active cases in the county, a sharp increase from last summer when there were estimated to be 80. The county’s case positivity rate, the percentage of those who test positive, is reported as high.

“If it’s below 10%, we’re winning. If it’s above 10% we’re losing, and it’s been above 10% since early August,” Williamson said.

How do we improve? Williamson says the answer is in increasing immunity levels. To reach herd immunity and get the virus under control, the percentage of the population who is immune needs to reach between 80-90%. Right now, Texas is at 70.89% and Wichita County is at 45.03% immunity.

“Natural immunity and vaccine-induced immunity, appear to me, in Wichita county [based on] observational data to be about the same,” Williamson said.

The fundamental difference between natural immunity and vaccine-induced immunity, Williamson says, is safety. To explain, he uses an analogy about being stuck on the fifth floor of a building after the elevator goes out.

“You have two choices… if you jump out the window, you will arrive at the ground floor. You may not survive, you may be injured or you may be extremely lucky and have no consequences. [If] you go down the stairs, you’ll be sore and tired but get to the bottom, and that’ll go away promptly, and you’ll be just fine,” Williamson said. “Natural immunity is very, very, very risky and has ugly, ugly consequences. Vaccine immunity is safe [and] effective.”

The Delta variant has led to a surge in cases over the summer, but if it follows the expected pattern, it should die down as fall sets in. This is based off of flu-related strains and also what was observed about the virus last year.

“This surge is going to end, I believe, in the first couple weeks of October…. We will continue to have cases but the surge will be over,” Williamson said.

Hello hello! I’m Emily Beaman and come this fall, I’ll be the news editor and social media manager for The Wichitan! A couple of fun facts about me:...