Authors in Voices 2020-21 share their creative process

September 15, 2021

The new 2020-21 edition of MSU Texas literary journal Voices features short story authors, poets and visual artists, seven of whom are award winning. Meredith Berend, criminal justice graduate and Vinson award-winning author of the poem “Junk Drawer Woman” said she was surprised to have been honored in the final year of the Vinson award.

“I turned my stuff in, my poems, on a whim and I just wasn’t expecting it. I ended up getting a phone call back in March and I cried a little bit, a lot,” Berend said. “I just think it’s a really big honor and as somebody who enjoys creative writing and thinks that it’s really really important. I really appreciated the [Vinson] award, and I wish it could have continued on…”

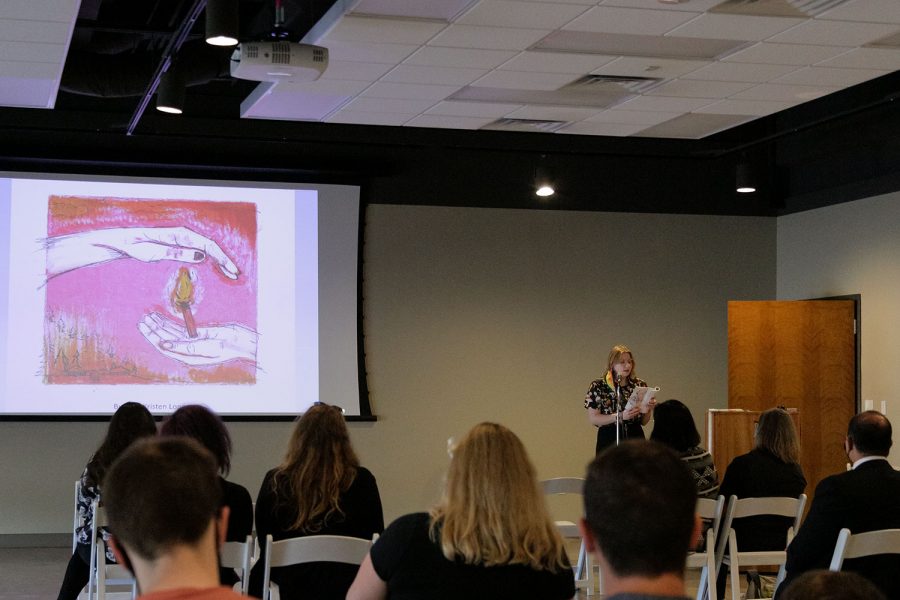

Berend said that she had a lot of encouragement from others at MSU and that her advice is to write regardless of whether something comes from it. She is not always confident in her poetry but received an award nonetheless. The President’s award also was given to poems Carson Owen’s “to be buried under glitter” for first place, Sadie Bartels’ “The Leviathan” for second place and Erika Cooper’s “North” for third place. Kristen Longo, art senior and writer of the poem “Talking to the Moon” in Voices 2020-21, agreed with this sentiment.

“Don’t be afraid, because there’s always people who don’t like your work, but then for every one person who doesn’t like it, 20 more are gonna love it,” Longo said

Berend and Longo’s works appear in Voices 2020-21 along with 50 other works, including the cover. Being published means that these writers and artists will have their work interpreted by a much larger audience, which is important for artists like Berend who seek to make commentary with their poetry.

“People have interpreted [‘Junk Drawer Woman’] differently, but for me, it’s about generational connections between women and their families,” Berend said. “Some people have interpreted it as a positive poem. Some people have thought it’s more of a negative one. I won’t say what it’s supposed to be because poetry is open to interpretation.”

This open interpretation means that more readers can connect with a literary work. Regardless of whether a reader’s interpretation matches up with the author’s interpretation, there is a level of vulnerability that goes along with sharing art. Longo said that artists should try to publish their work even if it’s difficult to show this vulnerability.

“It’s very scary putting yourself out there because these are almost like diary entries, essentially. They’re so full of emotion and I feel like that’s how it is for a lot of writers. It’s just kind of an outlet for whatever they’re feeling and that can be very scary to have that door open for the rest of the world to just walk on in.” Longo said. “I guess my advice would be to just open the door, you know.”

Opening this door can be an essential part of expressing oneself, Berend said. Creative writing and poetry can become not only part of processing thoughts and emotions but also part of helping others do the same thing. This is something that Adrienne Pine, author of the short story “Mother,” said she discovered in her writing and submission process.

“Writing it was part of my grieving process. I wrote it out of a deep place in myself. Yet readers identify with it. So I realize that my situation was not so singular after all,” Pine said.

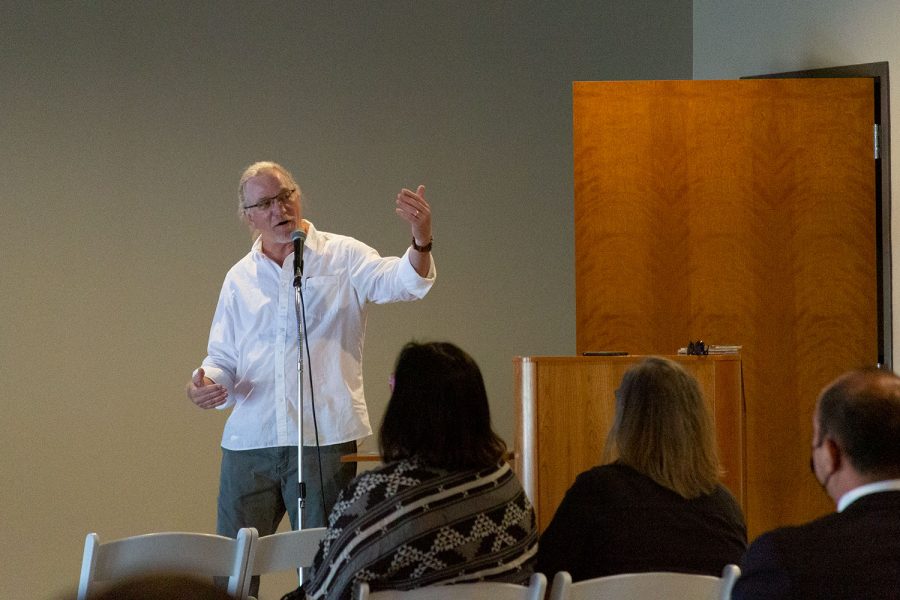

In this way, creative writing and poetry help not only the artist but also the reader. Advisor to Voices and associate professor of English John Schulze elaborated on this as well how the writing process can become part of the grieving process.

“Writing is an active discovery. You don’t always know what you’re going to write when you sit down to write, but inevitably you find out, ‘oh, that’s what I needed to write in order to heal.’ That’s the way I look at it,” Schulze said.

This healing comes from a place of complete honesty. That honesty is captured in Pine’s short story about her complicated relationship with her mother, a story that wasn’t easy for Pine to write.

“In order to write an essay as painful and personal as ‘Mother,’ I had to get to a place where I didn’t [censor] myself by worrying how readers would react to it. I cannot think about the reader or the publishing process or any of that while I am writing,” Pine said. “If I did, I wouldn’t be able to do it. I have to feel safe and know that I am not going to be interrupted. I try to listen to and follow my inner voice.”

While Pine said her writing process was a part of grief, Natalie Coufal, creative writing graduate student at Sam Houston and author of the short story “Blinding Brilliant,” said that stitching together the different parts of her story was like patchwork quilting.

“The writing process involved taking notes while I listened to my twin sister discuss her stay at a mental institution in College Station. All this while our kids played in the kiddie pool together. As always, I worked with bits and pieces of memory to reconstruct an experience. All the pop culture references were pieces of memory that I thought of while ruminating on the material from my sister,” Coufal said. “I feel memory is all I have. I don’t have creativity.”

Coufal’s short story won her first place in prose for the President’s award. Second place prose was awarded to Colin Scanlon’s “Twitter DMs From a Satanist,” and third place prose was awarded to Pine’s “Mother.”

“I didn’t expect to win. I feel honored by [the President’s] award and I appreciate the effort put in by the editors. But I am not satisfied in the sense that I know my craft can improve. I just have to put in the time and work and slowly improve,” Coufal said. “It’s like my sister when she makes her fancy cakes. Each cake makes her learn something. Each essay makes me learn something.”

Schulze said that it was gratifying to see his students, the editors of Voices, put together this issue. The editors are responsible for choosing which works make it into the issue and who stands out enough to be recognized with an award. Schulze also noted a common theme of vulnerability in many of the works chosen for this edition of Voices.

“This year, I would say, there was probably more vulnerability… because lots of people are going through issues… with the pandemic, and the way it has affected lives in numerous ways,” Schulze said. “Not all writing is healing… but this kind of creative writing [is], especially the creative nonfiction essays. I see writing as very therapeutic and we’re all trying to heal. I think that’s what this issue [of Voices] brings to the table: this sense of trying to make things better for ourselves.”

Excerpts from some of the mentioned works:

Junk Drawer Woman by Meredith Berend

“That’s what matters, she says, that we never melt,

but I watch her place a hand over her chest where

the heart’s meat boils from the inside-out upward

toward thin flesh, flinch as she feels the antique match

left behind by her mother and her mother’s mother

and a million mothers before her all made up

of everything but the kitchen sink, their matches

lit over gas stoves and fireplaces with lighter fluid

perfume, each one a slow burn that catches

the next match long after the flame has died.”

Blinding Brilliant by Natalie Coufal

“I’ve scribbled away at my spiral notebook; a mess of chicken-scratch words and phrases gawks back at me, a visual of the frenzy it took to jot them down. I scrawled so hard, the words are like braille, or scrimshaw– they have dimension and meaning, and I’m depending on it. It’s as bright as hell out here; when my eyes look up to the pool, my pupils shrink in pain. My hands brush up and down my homemade braille. I don’t know anything, but everything is blinding brilliant.”

Mother by Adrienne Pine

“I didn’t want to provoke her. I wanted her to love me, but she didn’t. She constantly found fault. Something I did or said, or something I didn’t do or should have done was always setting her off. Maybe she was right. Maybe deep down I was a bad person, pulling the wool over everyone’s eyes. The truth was that I hated my mother, and at the same time, I loved her with a painful love.

It took me a long time to learn to protect myself. It took distance. It took silence. It took decades.”