With enrollment numbers at an all-time high and the economy operating on a steady incline, 2007 was financially bountiful for the Mustangs. As the year turned, the university capitalized on the boom in enrollment, significantly altering admission standards in hopes to refine the quality of the student body.

But what a difference a year can make.

With the new year, 2008 brought with it the Great Recession, the largest economic downturn since the 1930s. As the nation’s economy began to crumble, so did enrollment numbers. State funding began its steady decline, leaving the university to operate for two years on reserve finances. Eight years later, however, it seems MSU is still feeling the affects of the recession. Operating on little state funding with no remarkable increase in enrollment, concerns turn, once more, toward a product 2008’s series of changes — the altered admission standards.

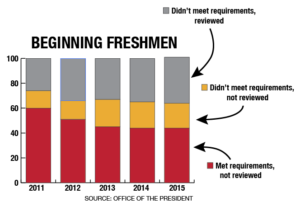

Though standards became more rigorous in 2008, faculty and administrators remain concerned about whether the standards, which involve standardized test scores and class rank, are truly benefitting the university. After the Faculty Senate received admission statistics in January of 2016, members saw that the number of students who failed to meet admission standards, but were still admitted with review, increased. While the concern about why so many students are ill-prepared remains at the forefront of consideration, some question as to why these students are admitted in the first place.

“I’m not entirely sure I know how to answer that,” Suzanne Shipley, university president, said. “At this time, we’ve assembled an admissions and financial aid task force to see if we can’t get some answers. It’s a far more complex issue than many people realize. Test scores change. The way people are tested change. Perceptions of the validity of these tests change. It’s difficult to determine a student’s preparedness by one or two numbers.”

Some students, however, have their own thoughts as to why these potentially less-prepared students have become their peers.

“When is it not about money?” Abbey Gipson, nursing freshman, said. “I understand that state funding depends on how many people we have, but where do you draw the line on student quality over quantity? We have to decide, at some point, what’s more important.”

According to the minutes of Faculty Senate meetings, the matter was first addressed in January of 2016, when David Carlston, chair of the Faculty Senate, voiced his initial concerns.

And information, compiled by the Faculty Senate, indicates that the number of students that did not meet standards, but were still admitted with, or without, review has increased from 149 students in 2011 to 285 students in 2015. As of fall 2015, 45 percent of incoming freshmen did not meet admission standards.

“As to why these students have been admitted, I don’t know,” Carlston said. “This is a very careful subject, and, until we have all the information, the answers you get are likely to be of a political nature. The trend of students entering the university through advised admissions was fairly steady up until 2011, but now that it has ‘stair-stepped,’ we’re really hoping to gather better data that allows us to quantify the preparedness of these students.”

The concern, however, was not addressed again until the Faculty Senate meeting of April 2016, when Shipley voiced a concern that there may be a perception amongst the faculty that students were less prepared than they have been in the past.

“When faculty tell me they have issues, I very much want to address them,” Shipley said. “After getting to know the senior faculty on a one-on-one basis, they began to explain that students were starting to do poorly on assignments that they previously weren’t.”

According to Shipley, this type of issue extends beyond any one university’s control, affecting schools all across the state. Yet, neither West Texas A&M University or Tarleton State University, neighboring schools of similar size, have reported any form of concern according to admissions officials on those campuses.

“You’d be hard-pressed to find a university who wasn’t facing this issue,” Shipley said. “The skills being taught in high schools are changing. It may be true that, over time, high schools are beginning to lack in teaching certain skills, but excelling in others. In my day, it’s safe to say the priority was on the basic skills, such as mathematical literacy, reading, and writing. However, the new generations excel in the fields of technology, communication, and leadership skills. I believe, in institutions of higher learning, we’re trying to transition, the best we can, to placing an equal emphasis on both. Flexibility is important, but nobody is perfect. It’s difficult.”

However, Jessyca Wagner, member of the admissions and financial aid task force, said she believes it is less the student’s technical abilities, and more the work ethic and emotional maturity of the students that come into question when discussing readiness.

“What I notice is that students appear very needy, sometimes,” Wagner said. “I mean, you can’t generalize. There are plenty of students who are more than capable of doing the work for themselves, but I have seen more than a few students who want to be spoon fed the material.”

Members of the task force, who have yet to set a time to meet, hope to discuss some form of solution and determine why the issue has progressed.

However, Mark Farris, mathematics professor, has his own theory.

Bringing into question the validity of standardized exams, including the Texas Success Initiative, Farris points out that the number of students who are placed in freshman level mathematics courses has decreased by 10 percent since 2013, while the number of students who are placed in developmental math courses has increased by 94 percent in the same time span.

“There are people who take developmental courses by choice, but the majority of people in those courses are people who did not meet the state standards that deem them ready to take a four-credit math course,” Farris said. “The bottom line is that the TSI isn’t sorting people effectively. An exam might say this person is ready for a freshmen level course, but in actuality, they’re just not. They aren’t prepared for the material, and it’s not always solely dependent on mathematical ability.”

“One of the issues you face with a university like Midwestern is that you have full-time students, working 30 hours a week,” he continued. “Well, whether or not that student comes to class and does the work makes all the difference, and sometimes they’re stretched almost too thin to really succeed. How do you form a lecture that accommodates to half the class that isn’t ready, and the other half that is? It’s just an overall disservice to the students.”

Professors are not the only ones to make observations that question the readiness of some students.

Megan Baltusis, early childhood education freshman, said she believes the quality of her own education could be compromised by the issue.

“I actually saw some kid in one of my classes ask the teacher what minimum wage was,” Baltusis said. “He wasn’t asking for a dollar amount, I mean he actually asked for a definition of what minimum wage was. He had no idea. That’s something that should be common knowledge by the time you’re in college, and when the professor is taking 15 out of the 50 minutes to explain what it is, that’s time that could have been better spent on something more in-depth and pertaining to the curriculum. It just makes you question how that kind of thing has evaded someone for that long.”

Brian Zug • Oct 7, 2016 at 11:02 PM

nice