By Malcolm X Abram

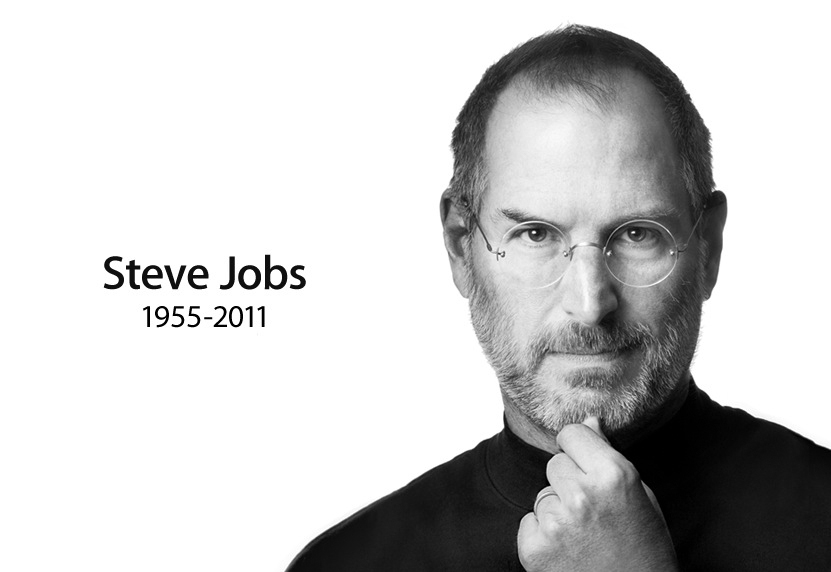

The list of industry, culture and entertainment shifts spurred by Steve Jobs and Apple is long and impressive.

He changed the music industry, the terrestrial radio industry, killed the record/CD megastores, changed the way billions of people acquire, share and enjoy information including music, and changed global culture, making the world just a little bit smaller.

Jobs, who died of pancreatic cancer Wednesday at age 56, is already being canonized as one of the major figures of the 20th and early 21st century.

“Steve Jobs’ impact on the music industry has been huge, especially for someone who wasn’t in the music business to start out with, and there are still some people in radio who haven’t quite accepted that things are very different now then they were five or 10 years ago,” said Liz Mozzocco, music director for WAPS-FM in Akron.

“Steve Jobs was huge in terms of bringing digital music to the public and giving them a direct route to purchasing music, and if you look at how many people were downloading music illegally, it’s pretty incredible that he was able to have success with the iTunes store.”

The digital music revolution (at least the profitable legal revolution) can be traced back to Jobs, whose ability to discern what the masses want before they knew they wanted it, and to then sell it to them in mass quantities with a flair for the theatrical, is only one aspect that made him a contemporary genius.

Back in 2001, music piracy was becoming a huge problem for the already flailing record industry.

Between CD-ripping programs, Napster and its variants and other online semi-secret portals, even users who wouldn’t know a torrent from a torte were discovering ways to download music for free.

The major record labels, who were still enjoying the popularity of compact discs, responded in typical fashion when one’s cash cow is being milked for free — they threatened and pleaded with users, sued students and housewives and wasted millions of dollars on faulty security programs for commercial CDs that made them almost useless to consumers.

Jobs saw the writing and the dollar signs on the wall.

As he had done in the past with home computers, he took something that already existed — there were several MP3 players already on the market — and he turned Apple’s version into the new standard.

“You can’t just ask customers what they want then try to give that to them,” Jobs once said.

“By the time you get it built, they’ll want something new.”

In 2001, Jobs and Apple introduced the first generation iPod.

Compared to the clunky MP3 and portable CD players on the market that didn’t fit smoothly in one’s pocket or purse, the iPod had a clean, attractive and unique design with simple controls.

And with the help of Apple’s considerable marketing push, it quickly became the “Kleenex” of MP3 players.

The brand’s name became synonymous with the product, as did the sight of folks grooving with the iPod’s signature white earbuds.

More importantly (and much more profitably), in 2003, after explaining to the major labels what much of the world already knew — that downloading was the future so they’d better join the revolution — Jobs introduced iTunes, a completely legal online music-buying storefront.

iTunes quickly became the norm with its flat 99-cent-per-song fee, giving consumers the ability to cherry-pick the tunes they wanted and the feeling of control while Apple essentially took the means of distribution away from the big majors.

Soon once-powerful mega chains such as Tower Records and Virgin were shuttering their doors and leaving music geeks to find local independent record stores that were able to carve out niche customer bases.

“I’m all for progress,” said Scott Shepard, owner of Time Traveler records, a 30-plus-year staple in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. “Unfortunately on my end of it, it wasn’t a positive thing for me.

“Stuff like the iPod, iTunes and burning stuff is basically what put an end to this kind of shop,” he said. “The ‘90s were incredible and the first couple of years of the 2000s were great, but around 2002-2003, it started declining and continues to decline.”

Shepard, who called Jobs a great innovator, said he noticed when the big chain stores began dying and hoped it would boost his business.

However, in recent years, he said it’s his niche clientele of collectors who are still buying deluxe reissues of albums on CDs and vinyl enthusiasts who are mainly keeping him afloat.

“Those are the customers that keep us going, but anybody who comes in here under 30 is looking for vinyl,” he said.

The impact of the iPods and iTunes on global music culture is equal to and arguably greater than the invention of the phonograph, the portable radio and any previous musical format from reel-to-reel and eight-tracks to the now nearly obsolete compact disc.

iTunes revived the single, which most of the major labels had abandoned.

Many established artists were skeptical of the iTunes model. U2, the Beatles, Metallica, Madonna, AC/DC and others raised in the album era resisted it for years, but nearly all eventually came around.

However, AC/DC and Garth Brooks apparently still are not interested, and earlier this year, Jon Bon Jovi directly blamed Jobs for killing the music industry.

As iPods’ hard drives grew exponentially from holding 1,000 songs to upward of 30,000 songs and the iTunes library continued to grow, a generation of consumers have been suitably trained to purchase music legally with Apple. iTunes surpassed 10 billion downloads in February 2010.

The iPod, iTunes and now iPhone triumvirate has also had a huge impact on terrestrial radio.

Mozzocco of WAPS said that the advent of the iPod shuffle and personal playlists have also affected the way that radio programmers do their jobs.

“I think that the one thing that happened because of that is a lot of radio programmers had to acknowledge the fact that people’s musical tastes are a lot more varied than they realized before,” she said.

“I think people were always interested in all different kinds of music, but when you have the iPod shuffle making it so easy to change genres and put different tracks next to each other, it does change the way people listen to music.”

Mozzocco, who has been in terrestrial radio for a decade, said that much of the industry has been slow to accept that commercial radio is no longer the primary way that listeners discover new music and that programmers who still rely on being fed new music by labels and charts or by spying on their competitors’ playlists are immediately behind the curve.

“If I see a band at a show with a huge fan base and their music makes sense for us, we’re going to play it and I don’t necessarily have to wait (to see) who else has jumped on board with this because people have access to it in other ways,” she said.