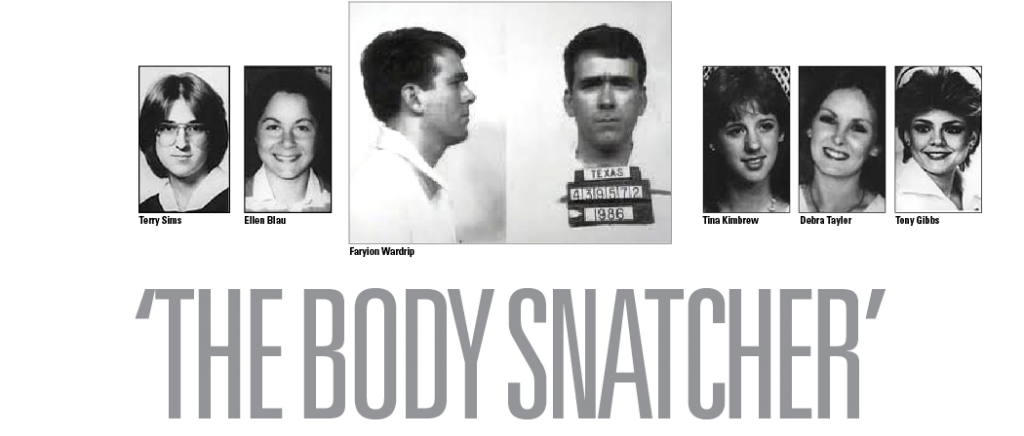

Killer of 2 students in 1985 not caught for 14 years

Blake Muse | Contributor

On television dramas from CSI to Law and Order, week after week, villains from rapists to serial killers get caught in 60 minutes. The reality is that catching a serial killer can take years, even decades, as investigators in Wichita Falls learned nearly 30 years ago.

Leza Boone returned to her home at approximately 8 a.m. on the morning of Dec. 21, 1984, after a pulling a double shift at Wichita General, the hospital she worked at. After she was unable to get in the locked front door, she called her landlord who found her friend, MSU student Terry Sims, dead on the bathroom floor in a pool of her own blood.

Sims noticed Faryion Wardrip “screaming at the stars” and when her assailant, Wardrip, saw her, he rushed to her. Sims locked the door, but Wardrip broke it down and “just ransacked her, just slung her all over the house in a violent rage,” Wardrip said, according to court documents. Sims died at the age of 20.

Allen Stilwell, a forensic pathologist, performed the autopsy on Sims and testified that she had eight stab wounds in the front of her chest, three stab wounds on the right side of her back and one stab wound on her left upper arm. Cuts on Sims’ fingers and hands indicated that she tried to fight off her attacker. Stilwell also testified that Sims had “tease wounds” inflicted by Wardrip to “get her attention.”

The crimes didn’t stop there. Approximately a year later, on Feb. 15, 1985, an electrician, Charles Haynes, who had gone to check on a transformer, found the body of Toni Gibbs off Highway 281. Gibbs had been bludgeoned to death with her clothes found in a trolley car near the field where her body was found.

Police charged Danny Laughlin with her murder after he obtain information on the case that he was not supposed to have.

He was later acquitted after his DNA didn’t match that of the crime scene.

Only seven months after the body of Gibbs was found, a county worker, Don Morgan, discovered the body of 21-year-old Ellen Blau, an MSU student and waitress who had moved from Connecticut to Texas. Decomposition had made any DNA or sexual assault evidence impossible. Blau had been missing for about a month.

The “body snatcher”—as he was known—killed again on May 6, 1986. Wardrip killed Tina Kimbrew by asphyxiating her with a pillow. Three days later, Wardrip called the authorities and admitting to knowing Kimbrew, but he also claimed to know another murder victim, Ellen Blau.

His claims about Blau were not investigated for almost 15 years.

He has never confessed to the crimes.

Wardrip only served 11 of his 35 year sentence for Kimbrew’s murder and was released on parole on Dec. 11, 1997.

After 15 years, new investigator John Little was handed the case, and it didn’t take him long to see some clues. Few noticed that a man named Faryion Wardrip claimed to know murder victim Ellen Blau BS that Wardrip had also been a janitor at Wichita General Hospital, where Toni Gibbs was a nurse. Sims body had also been discovered only two blocks away from Wardrip’s apartment, where Blau had been reported missing.

Even though DNA evidence had been left at the scene, investigators had no DNA to match it with for comparison, so Little had to get creative.

Wardrip moved to Olney, Texas after his parole, got remarried, became an active member of his church, and started working at Olney Screen and Door.

Across the street on Feb. 5, 1999, Little pretended to wash his clothes at a laundromat across the street. When he saw Wardrip go on a coffee break, Little placed a pinch of tobacco in his mouth and asked if he could use Wardrip’s coffee cup for spitting. Wardrip agreed.

Little then sent the cup to Genescreen for DNA comparison. It resulted in a match.

He was called in after the match was made by his parole officer.

Wardrip thought he was meeting his parole officer, but instead investigators waited for him.

Little questioned Wardrip about the murders, but Wardrip denied even knowing the victims until three days later. Wardrip later confessed to the murders of Sims, Gibbs, Blau, and even a victim that investigators didn’t know about. Wardrip said he was unsure of her name. Debra Taylor was identified as the victim and Wardrip said the murder occurred sometime in the mid 80s.

Originally given the death penalty, Wardip later appealed his case on the grounds that he had ineffective legal counsel and is now serving three consecutive life sentences.

Television shows might be distorting the reality of how long it takes to catch these killers, even if investigators have DNA evidence.

“[It takes] about a week or so,” Jake Taylor, a sophomore in computer science, said.

Students seem to understand that these shows are mainly for entertainment value, and not so much for their accuracy.

“I watch a lot of crime shows,” Brooke Long, a senior in mass communication, said. “I love them. They’re not incredibly accurate. The court and legal process isn’t very exciting so they have to vamp it up.”

Jake Taylor, sophomore in computer science, said even though crime shows are entertaining to watch, the creators have a tendency to overdo it.

“They exaggerate the abilities of the police department,” Taylor said. “I’m pretty sure they don’t get a gun.”

At one time, the Wardrip case was three separate investigations with little communication between the different agencies, and that slowed the process down.

MSU Chief of Police Dan Williams said, “We can be territorial, and we had a good idea it was the same guy, but we didn’t have any evidence to connect them to one another.”

This evidence didn’t turn up until District Attorney Barry Macha ordered a DNA test of the two semen samples from the Sims and Gibbs case to be tested for a match in March of 1990.

Chris Green, sophomore in graphic design, said a police agency’s success “depends on their willingness to let information out. Sometimes they might be competing to solve the crime first.”

Television crime dramas also leave out that a convicted killer who confesses can sometimes escape a lifetime of imprisonment. Wardrip was released on parole in December of 1997. Having served 11 years of his 35-year sentence, he appealed and escaped the death penalty.

Williams said the criminal justice system in America “by a long shot is not perfect, but it’s one of the best in the world.” Williams said in the 80s, legislative measures had been taken that gave a vast majority of inmates the opportunity to appeal their cases and get out on parole for “good behavior.”

Long said, “I agree with the appeal. Death is too good for people who commit heinous crimes. They deserve life with as many years with as little happiness as possible.”

When it comes to the topic of the death penalty, civilians might have a different opinion than that of the officers who see these crimes throughout the span of their career.

“I’m a death penalty supporter,” Williams said. “You find that most police officers are.”

After the murders in the 80s women bought guns, started locking their doors and stopped going outside at night. Today, students still take precautions.

“I lock my car. I don’t text when I go out to my car,” Long said. “I pay attention to my surroundings and recent activity.”

Serial killers, by definition, possess the ability to commit crimes and evade justice, a fact known all too well by investigators. The case of Faryion Wardrip took 15 years to solve, but that’s just half the battle. Even if you have DNA evidence, solving a crime takes longer than what is on TV.

“That’s just not reality,” Williams said. “High profile cases will be in the courts for years, and have automatic appeals all the way up to the Supreme Court. We have to work through every piece of evidence. We can’t afford to operate on half-truths.”

On Friday, April, 5, the Northern District of Texas ordered that habeas corpus relief be granted to Wardrip’s case. This was given to him because he claims the evidence should have shown him in a better light, such as highlighting his work for the prison newspaper.

Despite the outcome of a future trial, the death penalty sentence is now off of the table.